|

Nevada

Sage Grasshopper Wyoming Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 912

Distribution

and Habitat Click here for the printable version

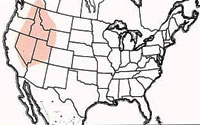

The Nevada sage grasshopper inhabits the deserts of the far West. It is distributed mainly in Nevada and Utah, but also occurs in adjacent states and the province of British Columbia. The preferred location of the species is in cold desert shrub areas where a variety of shrubs dominate the flora with several subdominant forbs and grasses growing in the understory. These diverse plants appear to serve as food at different times in the season for the Nevada sage grasshopper. Economic ImportanceHigh densities of nymphs (100 to 3,000 per square yard) and of adults (no absolute figures available) during the outbreak of 1938-51 in Nevada caused serious damage to shrubs, the dominant vegetation in the habitat of the Nevada sage grasshopper. The grasshoppers defoliated, barked, and killed host plants. Eleven species of native shrubs were fed upon, as well as forbs and grasses. The grasshoppers disrupted the natural biodiversity of the plant community by killing the shrubs and opened the land to soil erosion and invasion of noxious weeds. Extensive damage to vegetation reduced the amount of winter forage for livestock and wildlife. Several cases of severe damage to big sagebrush, budsage, and silver sagebrush occurred. Additionally, soils within and adjacent to the egg beds were denuded by the feeding of nymphal bands. Despite attempts to control outbreaks of this pest grasshopper, populations persisted for years. In Nevada the outbreak that began in 1938 lasted until 1951, a total of 14 years, while in western Utah an outbreak that began about 1989 did not end until 1996, a total of seven years. Swarms in Nevada that landed in garden crops completely destroyed plantings of corn, lettuce, onions, radishes, beets, and potatoes. The grasshoppers were not recorded as entering grain fields, but invasion of alfalfa and sweet clover fields caused minor damage. The Nevada sage grasshopper is a medium-sized species. The live weight of eight migratory phase males collected in Millard County, Utah in 1995 averaged 290 mg and eight females 565 mg (dry weight of males 96 mg, females 186 mg). Live weight of two solitary males collected in Millard County, Utah in 1998 averaged 264 mg and five solitary females 552 mg. Differences in live weight between migratory and solitary grasshoppers of the same sex were statistically insignificant. Food HabitsObservations of feeding of the Nevada sage grasshopper during the Nevada outbreak of 1938-51 revealed that migratory phase nymphs and adults were primarily shrub feeders. Of the shrubs attacked, five were preferred: big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), black sagebrush (A. nova), Douglas rabbit brush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus), spiny hopsage (Grayia spinosa), and shadscale (Atriplex confertifolia). Five less preferred shrubs included silver sagebrush (A. cana), bud sagebrush (A. spinescens), littleleaf horsebrush (Tetradymia glabrata), antelope bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata), and gray rabbitbrush (C. nauseosus). In addition, sporadic feeding was observed on 14 forbs and five grasses. Heavy feeding, however, occurred on downy brome, a common and abundant invader plant of western deserts. An interesting observation was made in the desert of Millard County, Utah of a solitary phase female that fed upon scarlet globemallow. On 19 June 1998, 10:34 a.m. DST (soil surface 105° F, air 68° F, clear), this grasshopper hopped from the ground onto globemallow and crawled around the plant tasting leaves and stems. It finally tasted and fed upon a young fruit for 9 minutes and then hopped back to the ground. This observation prompted examination of eight globemallow plants, all of which exhibited grasshopper injury to leaves, flowers, stems, and fruits. As the Nevada sage grasshopper was the only species of grasshopper feeding on forbs and shrubs inhabiting the site, its feeding on scarlet globemallow, a common plant in the Utah desert, provided evidence that this plant may be an important host. Unexpected results were obtained in laboratory food preference tests of the Nevada sage grasshopper involving 12 species of plants (two-choice tests). Four plants were preferred: young wheat leaves, dandelion, downy brome, and white sage (Ceratoides lanata). The ubiquitous downy brome, green in spring but dry and brown in summer, may serve as an important host plant for the nymphs. Seven less-preferred (less eaten) species were big sagebrush, gray rabbitbrush, scarlet globemallow, Gardner saltbush, kochia, alfalfa, and barley. One species, tansy mustard, was not fed upon at all. A definitive study of the food habits of the Nevada sage grasshopper has yet to be made. Results of the food preference tests and several field observations of feeding by adults and of damage by nymphs (dense bands of gregarious nymphs baring the ground of vegetation) provide evidence that the Nevada sage grasshopper is not solely a feeder of shrubs. Like dense hordes of several other species of grasshoppers, they exploit nearly all plants in the habitat rather than starve for lack of a preferred food. Shrubs appear to be a second choice of the Nevada sage grasshopper. Dispersal and MigrationDense populations of the Nevada sage grasshopper are extremely migratory. In Nevada in the summer of 1948, close observations revealed that swarms of adults traveled 2 to 4 miles in a day and from 40 to 75 miles during a season. After feeding in the morning, adults began migration whenever conditions were favorable for flight: clear sky, minimum temperatures of 70° F air and 85° F soil, and air movement of about 2 mph. A wind of 15 mph held swarms on the ground. The first flights of young adults were erratic and short and were interspersed with periods of crawling and resting. After several days of undirected flights, swarms began to move as coherent groups chiefly in a northerly direction and at heights of a few hundred feet. One closely observed swarm moved about 2 miles each day and traveled a total distance of 40 miles. Another swarm was observed to have flown a record distance of 15 miles in one day. Daily termination of flights was not observed. Swarms may be lifted several thousand feet in the air by warm summer updrafts. Sudden strong winds aloft may then transport the grasshoppers long distances. The presence of specimens of this grasshopper on Grasshopper Glacier in Montana in 1949 suggested that a long flight had occurred; the closest outbreak population in that year was in southwestern Oregon 600 miles west of the glacier. Flushed adults of dense populations have been observed to fly off beyond the observer's vision, but flushed adults in sparse populations usually fly short distances of 1 to 9 feet and at heights of 4 to 18 inches. The adults take off from the ground and usually land on the ground. They fly silently and straight but a few may turn at a right angle near the end of flight. The grasshoppers fly at various orientations to the wind: into the wind, with the wind, and crosswind. Like the adults, the nymphs of the Nevada sage grasshopper have notable migratory habits. Observations of their migrations were made in 1948 in Nevada. The young nymphs, instars I to III, moved erratically and independently of one another. The older nymphs, instars IV and V, migrated as coherent bands and usually moved northerly in the same direction as the previous year's adults. One band of nymphs was observed to have traveled 200 yards in one day and one-half mile in two weeks. Identification

The Nevada sage grasshopper is a brightly colored species (Figs. 6-8). The inner and lower areas of the hind femur are bright orange. The upper marginal and medial areas are tan and crossed transversely by three dark bars. The middle bar of the medial area is usually chevron-shaped. The hind tibia is blue. Diagnostic characters of the species are the large size and quadrate shape of the male cercus (Fig. 9) and the corkscrew twist of the lateral appendage of the aedeagus. In the closely related Melanoplus occidentalis, the cercus is slightly smaller and triangular with apex evenly rounded and the lateral appendage of the aedeagus is straight (needle-shaped). Adults possess long wings that extend 1 to 7 mm beyond the apex of the hind femur. Ashley Gurney described this grasshopper in 1949 and named it in honor of the late professor of entomology, Arthur G. Ruggles, University of Minnesota. Gurney recognized solitary and migratory phases that differ in body size and wing length with the migratory individuals having larger bodies and longer wings. Small differences in the color of adults exist between the phases. Markings of pronotum and hind femur of solitary adults tend to be gray rather than the bright orange of migratory adults. The nymphs are identifiable by their structures color, and shape (Fig. 1-5). 1 . Head with face nearly vertical, and colored usually solid tan, antennae filiform; compound eye with diagonal dark bar, light bar on each side of dark bar that extends nearly full width of eye; dorsal area of eye with relatively few large pale tan spots, ventral area with numerous small dark spots. 2. Prominent white or cream-colored crescent beginning on gena below compound eye and extending onto pronotal lobe. 3. Medial and upper marginal areas of hind femur crossed by three alternating dark and light bars. Hind tibia gray and fuscous. 4. Body marked by black stripes and cream and tan patches. HatchingThe Nevada sage grasshopper is an early-hatching species. Observations made in Nevada from 1940 to 1951 revealed that hatching began in years of normal weather as early as April 10. In a warm year in Smoky Valley, Nye County, Nevada, hatching began 1 April, 1938. Below normal temperatures delay hatching as much as 20 days. In 1998 in western Utah (Millard County, Steamboat Pass, elevation approximately 4,800 ft.) hatching was calculated to have begun on April 19 and continued until May 14. The hatching period ranged from two to three weeks. Nymphal DevelopmentIn the field the Nevada sage grasshopper develops through five instars and becomes an adult in approximately six weeks. Because of the early hatch, the grasshoppers are exposed at times to periods of cold weather which cause delays in their development. Reared in the laboratory at a constant 90° F, the Nevada sage grasshopper developed at the same rate as M. bivittatus and M. sanguinipes, approximately 23 days. Adults and ReproductionThe first adults of the Nevada sage grasshopper may appear as early as mid May or as late as mid June. A population near Carson City, Nevada (elevation 4,675 ft) on 19 May 1943 consisted of 60 percent nymphs and 40 percent adults; 75 miles north at Sand Pass, Nevada first adults did not appear until 15 June 1948. In Millard County, Utah, a population on 2 June 1995 consisted of 81 percent nymphs and 19 percent adults. Maturation was studied in the laboratory beginning with adults newly emerged on June 12 to 15, 1995. Source of the nymphs was a population of the migratory phase infesting Millard County, Utah. Two males and seven females were confined in a large cage (11 3/8 in cubed) furnished with a 15 W incandescent bulb turned on during the day and off at night. Day temperatures averaged 82° F and night 72° F. Eight days after becoming an adult a male was observed attempting to mate, but mating was not observed until the 11th day. After 21 days of adulthood, the first egg pod was sifted from the oviposition tray. Observations of life history made in Smoky Valley, Nye County, Nevada in 1938 revealed eggs of the Nevada sage grasshopper hatching on April 1. By the third week in May practically all of the grasshoppers were adult. Two weeks later (June 1) egg deposition began and continued until the latter part of July when few adults survived. The eggs overwintered and hatched the following spring. The eggs are pale yellow or pearl gray and 4 to 5 mm long. Pods are 1 to 1 3/4 inches long, and contain from 14 to 25 eggs (Fig. 10). Population EcologyEcological studies of the Nevada sage grasshopper have been limited mainly to outbreak populations. Early in adult life, the grasshoppers in dense populations begin to migrate 2 to 4 miles each day. In 1948 a closely monitored swarm located a few miles southwest of Denio, Nevada and measuring 2 miles wide and 8 miles long, began to migrate north early in July at a rate of 2 miles per day. The swarm traveled a total distance of 40 miles crossing into Oregon and colonizing an area on the eastern shore of a dry lake on July 21. There the grasshoppers lived out the rest of their lives. Published articles do not mention any dropouts from the migrating swarms. It is likely, however, that dropouts occur especially toward the end of the migratory period when some of the older females become gravid. These dropouts appear to disperse the species over wide areas of western deserts. Once a population increases to outbreak numbers, it survives at high densities for a relatively long time. In Nevada an outbreak continued for 14 years from 1938 to 1951; in Millard County, Utah an outbreak continued for a minimum of 7 years from 1989 to 1995, ending only because of a severe drought. Evidently the migration into new habitats each year safeguards the grasshoppers from buildups of predators and pathogens. Sparse populations of the Nevada sage grasshopper have been briefly studied in Millard County, Utah. Densities of six populations observed along a 30-mile transect south and east of Sevier Lake in 1998 were estimated to range from less than one to one young adult per square yard. The grasshopper's high frequency of occurrence indicated a low density infestation of 250 square miles; perhaps under favorable conditions the grasshoppers will again increase to outbreak proportions. This area was infested by the outbreak of 1989-95, which ended when a severe drought began in July 1995 and lasted through 1996. The nymphs were not observed in the spring of 1996. Presumably most of the eggs laid in the summer of 1995 desiccated and died from lack of water. A few eggs evidently survived in drainages, as small numbers of nymphs were found in such areas in 1997 but none in the upland, which in 1995 was heavily infested with both nymphs and adults. Daily ActivityThe Nevada sage grasshopper is a geophilous species, spending most of its time on the ground. In spring when nighttime temperatures often dip to 45° F, nymphs sit horizontally on ground litter sheltering under shrub canopies. On summer nights, the adults at night appear to rest horizontally on the ground without seeking special places for shelter. About an hour after sunrise both nymphs and adults begin to bask by "flanking." They turn a side perpendicular to the rays of the sun and lower the associated hindleg to expose the abdomen. During cool weather (50° to 70° F air temperature), the grasshoppers may bask for three hours. General activities begin after the basking period. Some grasshoppers, however, may begin certain activities sooner. In Nevada, migratory phase nymphs were observed to feed from 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. at air temperatures of 50° to 80° F. After feeding in the morning, the migration of nymphal bands began when soil surface temperatures reached 80° to 85° F. Also swarms of adults fed heavily in the morning before migrating. Reproduction began when the migratory period ended and the majority of females were ready to deposit eggs. The females oviposited from 8 a.m. until noon at soil temperatures of 85° to 130° F. Ovipositing females exhibited a high degree of gregariousness; often more than 100 simultaneously deposited their eggs in a small area. In western deserts, summer temperatures often exceed 100° F air and 140° F soil surface. To avoid temperatures above their preferendum and tolerance, adults of the Nevada sage grasshopper make behavioral adjustments. In Millard County, Utah, adult grasshoppers in sparse populations were observed to crawl on the ground into the shade of shrubs or to climb several inches into the canopy of shrubs. In dense populations adults climbed to various heights and covered much of a shrub, which often had been defoliated and barked. After temperatures decline in late afternoon, the grasshoppers become active and remain so at the normally and relatively high evening temperatures. At sunset they sit horizontally on bare ground and plant litter. Night activity has not been observed, but it is probable that some adults may move about and even feed. Cowan, F.T. 197 1. Field biology of the migratory phase of Melanoplus rugglesi (Orthoptera: Acrididae). Annals Entomol. Soc. Am. 64: 574-580. Gurney, A.B. 1949. Melanoplus rugglesi, a migratory grasshopper from the Great Basin of North America. Proceedings Entomol. Soc. Washington. 51: 267-272. |