|

Chemical analysis of plant tissue is also an important technique in the

diagnosis of nutritional

disorders. In annual crops, tissue analysis is most often used in

‘trouble-shooting’ rather than in the recommendation of fertiliser rates.

However, if the tissue samples are collected early in crop growth and analyses

are completed quickly, a corrective fertiliser application may be possible

within the same season.

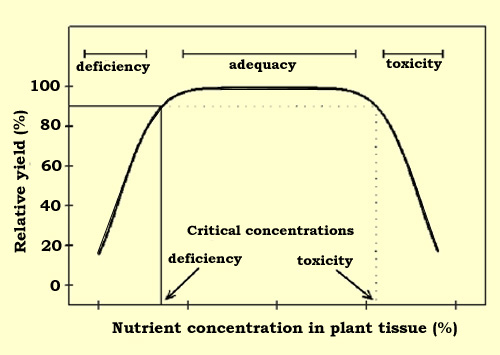

The interpretation of tissue analyses is based on established

relationships between crop yield and nutrient concentrations in plant tissue

(Figure 1). Critical concentrations are those which separate the sufficient

(healthy) range from the deficient or toxic range. For practical purposes,

critical concentrations are defined as those concentrations associated with 90%

of maximum yield. Between these concentrations is the range of concentrations

required for healthy growth.

|

Figure

1. Schematic relationship between relative yield and concentration of a

nutrient in plant tissue. |

The relationship between crop yield and concentration of a

particular nutrient in plant tissue may be determined by means of nutrient

solution culture experiments, glasshouse pot experiments, or field experiments.

Generally, field experiments are considered the best (Bates, 1971), but are

considerably more expensive than solution culture and pot experiments. They also

depend on the availability of sites which are deficient in each of the nutrients

to be studied. The values given in this publication have been derived from

solution culture experiments. Where possible, their reliability has been

validated under field conditions.

A certain part of the plant rather than the whole plant, is

usually collected for analysis. Leaves are usually considered the most

satisfactory parts. Because leaves continue to accumulate some nutrients with

age, it is important that nutrient concentrations in leaves of the same

physiological age are compared. In many annual crops, the blade of the youngest

fully expanded leaf is selected as the ‘index’ tissue for analysis. However,

sweetpotato leaves may continue to expand throughout much of their life, so

their physiological maturity cannot be judged easily on the basis of full

expansion. The many studies referred to in this book have selected different

leaves or parts of the vine for analysis, which makes the information difficult

to compare. For the critical concentrations quoted here, the blades of the 7th

to 9th youngest leaves have been selected as the index tissue. They were

selected as being sufficiently responsive to disorders of both mobile and

immobile nutrients, and having less variable nutrient concentrations than

younger leaves.

|

Critical nutrient concentrations for deficiency and toxicity, and the

adequate concentration ranges for sweetpotato, measured in the 7th to

9th open leaf blades from the shoot tip, sampled at 28 days from

planting. Data were obtained from experiments in solution culture using

cv. Wanmun.

|

|

Nutrient |

Unit |

Critical

Concentration for Deficiency |

Adequate

Range |

Critical

Concentration for Toxicity |

|

N |

% |

4.2 |

4.3 - 5.0 |

|

|

P |

% |

0.22 |

0.26 - 0.45 |

|

|

K |

% |

2.6 |

2.8 - 6.0 |

|

|

Ca |

% |

0.76 |

0.90 - 1.2 |

|

|

Mg |

% |

0.12* |

0.15 - 0.35 |

|

|

S |

% |

0.34 |

0.35 - 0.45 |

|

|

Cl |

% |

- |

- |

0.9 - 1.5 |

|

Fe |

mg/kg |

33 |

45 - 80 |

|

|

B |

mg/kg |

40 |

50 - 200 |

220 - 350 |

|

Mn |

mg/kg |

19 |

26 - 500 |

1600* |

|

Zn |

mg/kg |

11* |

30 - 60 |

70 - 85 |

|

Cu |

mg/kg |

4 - 5 |

5 - 14 |

15.5* |

|

Mo |

mg/kg |

0.2 |

0.5 - 7 |

|

| *These critical concentrations have been

found, on occasion, to be inconsistent with field observations, or to

vary with environmental conditions. Refer to fact sheets on specific

disorders for a full discussion. |

Apart from the physiological age of the leaf, as indicated by

its position on the plant, tissue composition may vary with the age or stage of

development of the crop. For instance, some researchers have found the critical

concentration for N deficiency to decline with crop age. Caution should

therefore be exercised in applying the critical concentrations established for

young plants to tissue taken from older crops. With regard to the values given

in the above table, it should be noted that the sweetpotato plants grew more

rapidly under experimental conditions than could be expected in the field. These

plants may be equivalent to crops from 6 to 10 weeks of age, depending on the

temperature and water supply experienced by the crop. In any case, they

represent crops prior to the stage of rapid growth of the storage roots. From

the point of view of applying corrective measures to the crop on the basis of

the diagnosis, it is preferable to sample the crop at as early a stage as

possible. However, in many instances, symptoms of a disorder may not appear

until advanced stages of crop development. In such cases, tissue analysis will

still be valuable, but discrepancies arising from plant age should be borne in

mind when interpreting the results.

Environmental conditions may further affect the

concentrations of nutrients found in leaves. The concept of critical nutrient

concentration requires that the nutrient of interest is the only factor limiting

growth when the plant material is sampled. It has been shown that water stress

can change the nutrient concentrations in leaves, and that plants take some time

to recover normal concentrations after restoration of adequate water supply. It

has been recommended that a period of several weeks without water stress should

precede the sampling of tissue. This is not practical in many situations, but

users should be mindful of this potential source of error.

To collect leaf samples, the blades are removed without the

petiole, and should be dried as soon as possible after sampling, using gentle

heat (eg. 60-70oC for 48 hours) or microwaving. If samples must be

stored for more than a few hours before drying, it is preferable to keep them

cool (eg. in an ice box, but not in contact with water) to minimise the weight

loss due to respiration of the living tissue. It is important to sample leaves

that have not been contaminated with soil. If the leaves are dusty, they may be

gently rinsed and blotted dry, but extended immersion in water and rubbing

should be avoided. Only distilled or deionised water should be used.

When sampling a crop, it is best to take a composite sample

of leaves from several plants which are equally affected by the symptom of

concern (Reuter and Robinson, 1986). If the crop is not uniformly affected,

several samples could be taken, each from small, uniform areas of the crop, from

the most to the least affected. The symptoms observed, and the level of

severity, should be recorded for each sample, and the samples clearly labelled.

Source: O’Sullivan,

J.N., Asher, C.J. and Blamey, F.P.C. (1997) Nutrient Disorders of Sweet Potato.

ACIAR Monograph No. 48, Australian Centre for International Agricultural

Research, Canberra, 136 p. |

Previous Page:

Diagnosing nutritional

disorders

Next Pages:

Visible symptoms of nutritional

disorders

Soil analysis

Related topics:

Soil

management

Plant

nutrients

Fertilization

Causes

of nutritional disorders

Correcting

nutritional disorders |