|

|

Class |

Secernentea |

|

Order |

Tylenchida |

|

Superfamily |

Tylenchoidea |

|

Family |

Meloidogynidae |

|

Genus |

Meloidogyne |

The degree of damage depends upon the population density of

the nematode, taxa present, susceptibility of the crop, and environmental

conditions, such as fertility, moisture and presence of other pathogenic

organisms, which may interact with nematodes. In sweetpotato an estimated annual

yield loss of 10.2 % was reported. In susceptible varieties pathogenicity

of Meloidogyne incognita showed a 50% storage root reduction at

a population density of 20,000/cm3. Aside from yield loss, cracking can make

storage roots unmarketable.

The root-knot nematode,

Meloidogyne incognita, is worldwide in distribution. It is widespread in

Asia, Southeast Asia and usually occurs in warmer areas. In some

countries, M. javanica is more dominant.

Above-ground symptoms exhibited by sweetpotato plants due to

root-knot nematode include poor shoot growth, leaf chlorosis and stunting.

Galling of rootlets and severe cracking of storage roots on some varieties or

formation of small bumps or blisters on other varieties are important

below-ground symptoms in sweetpotato. There may also be brown to black spots in the

outer layers of flesh which are not evident unless the storage root is peeled.

Presence can be diagnosed by the pearl-like swollen female

nematodes in flesh of storage roots or in fibrous roots, within the galls or

dark spots.

M. incognita is sexually dimorphic.

The female is saccate to globose,

0.4-1.3 mm. long, and usually embedded in root tissues which are often swollen

or galled. Its body is soft, pearl white in colour and does not form a

cyst. The neck protrudes anteriorly and the excretory pore is anterior to the

median bulb and often near the stylet base. Its vulva and anus are terminal,

flush with or slightly raised from the body contour, the cuticle of the terminal

region forms a characteristic perineal pattern, which is made up of the stunted

tail terminus, phasmids, lateral lines, vulva and anus surrounded by cuticular

striae; the pattern is often characteristic for individual species. The female

stylet is shorter, 10-24 Ám usually 14-15Ám, and more delicate with small

basal knobs. The paired gonads have extensive convoluted ovaries that fill most

of the swollen body cavity. There are six large unicellular rectal glands in the

posterior body which produce a gelatinous matrix, which is excreted via the

rectum to form an egg sac in which many eggs are deposited.

The male has long, thin, cylindrical shape of a worm but the

lip region has a distinct head cap, which includes a labial disc surrounded by

lateral and medial lips. The head skeleton is usually weaker and the stylet less

robust and shorter, 18-24 Ám long for many species. Infective second stage

juveniles, often free in the soil, are usually 0.3-0.5 mm long; they are less

robust, the stylet is delicate with small basal knobs, under 20 Ám long, and

the head skeleton weak. The median oesophageal bulb is well developed and the

oesophageal glands are extensive, overlapping the intestine for several body

widths, mainly ventrally; the tail is conoid, often ending in a narrow rounded

terminus, but tail length is variable, 1.5-7 anal body widths between species,

it often ends in a clear hyaline region, the extent of which can help to

distinguish species. (Sasser and Carter, 1985).

In addition to the adult and egg, there are four juvenile

stages and four moults in the life cycle of M. incognita. The first stage

juvenile develops in the egg, and the first moult usually occurs within the

eggshell, giving rise to the second-stage juvenile, which emerges free into the

soil or plant tissue. Once the nematode begins feeding on tissue of a favourable

host, the second, third and fourth moults occur giving rise to the third, fourth

and fifth or adult stages, respectively. Between moults, there is further growth

and development of the nematode, with concurrent development of the reproductive

systems in the two sexes. Upon maturity, the female deposits eggs and the life

cycle is repeated. Its life cycle is similar to Heterodera but the

generation time, 4-8 weeks, is shorter.

M. incognita has a very wide host range including weeds. Meloidogyne

spp. attack virtually all plants.

Cultural control

Crop rotation.

Non-host crops or resistant crops can be planted when nematode population is

high.

Addition of

organic amendments. Chicken manure is very effective reducing nematode egg

masses by 56%.

Use of trap crops

and antagonistic crops. Planting Tagetes erecta and Crotolaria

spectabilis in nematode infested soil is effective against the root-knot

nematode

Biological control

Paecilomyces lilacinus, a fungal egg parasite, was found effective

against root-knot attacking sweetpotato. The parasite reduced egg masses by

about 50%.

Host-resistance

There are many varieties of sweetpotato found resistant to the root-knot

nematode. Some of these are: W-86, L4-89, BPA-4 and Sinibastian, Jasper,

Jewel, Miracle, Georgia Red, Garcia Yellow and Travis. However, some populations

of M. incognita can infect even some of the resistant cultivars.

Chemical control

Several nematicide have been very effective against the root-knot nematode in

sweetpotato. Examples are Nemagon, Mocap, Dasanit, Nemacur, Furadan, Temik,

Vydate.

Evans, K, D. L. Trudgill and J. M. Webster. 1993. Plant Parasitic Nematodes

in Temperate Agriculture. University Press, Cambridge. 648 p.

Galano, C. D., R. M. Gapasin and J. L. Lim. 1996. Efficacy of Paecilomyces

lilacinus isolates for the control of root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne

incognita (Kofoid and White) Chitwood) in sweet potato. Annals of Tropical

Research 18: 4-12.

Gapasin, R. M. and R. B. Valdez. 1979. Pathogenicity of Meloidogyne

spp. and Rotylenchulus reniformis on sweet potato. Annals of Tropical

Research 1:20-26.

Gapasin, R. M. 1984. Resistance of fifty-two sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas

(L.) Lam.) cultivars to Meloidogyne incognita and M. javanica.

Annals of Tropical Research 6: 1-19.

Sasser, J. N. and C. C. Carter. 1985. An Advanced Treatise on Meloidogyne.

Vol. I: Biology and Control. North Carolina State University Graphics. 422 p.

Sasser, J. N.

1989. Plant Parasitic Nematodes: The Farmerĺs Hidden Enemy. University

Graphics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N. C. 115 p.

Contributed

by: Ruben Gapasin |

Taxonomy

Economic

importance

Geographical

distribution

Symptoms

Morphology

Life

cycle

Host

range

Management

References

Galls

and egg masses of root-knot nematodes on fibrous roots (left).

Galls on sweetpotato roots are often much smaller and difficult to see (W.

Martin, APS).

Increasing yield reduction and storage root damage with increasing

nematode population.

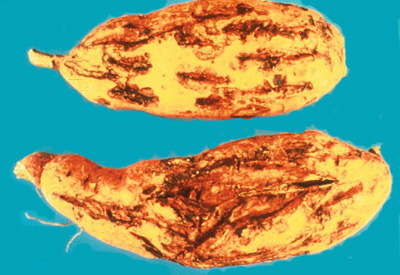

Cracking

on storage roots due to root-knot nematode (G. Lawrence, APS).

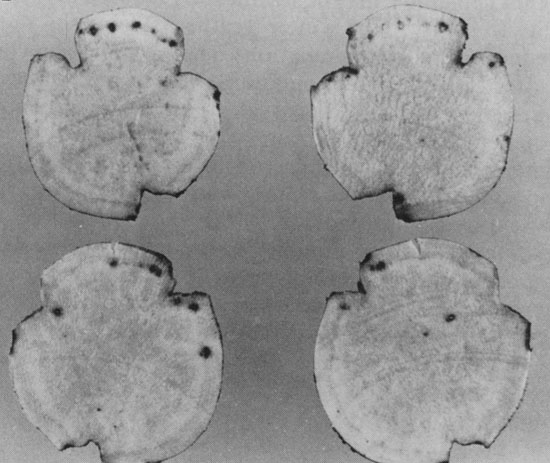

Dark spots in the outer layers of the flesh, each containing a nematode

surrounded by dark cork tissue (G. Lawrence).

Subcortical spots which were not evident until the roots were peeled (W. Martin, APS).

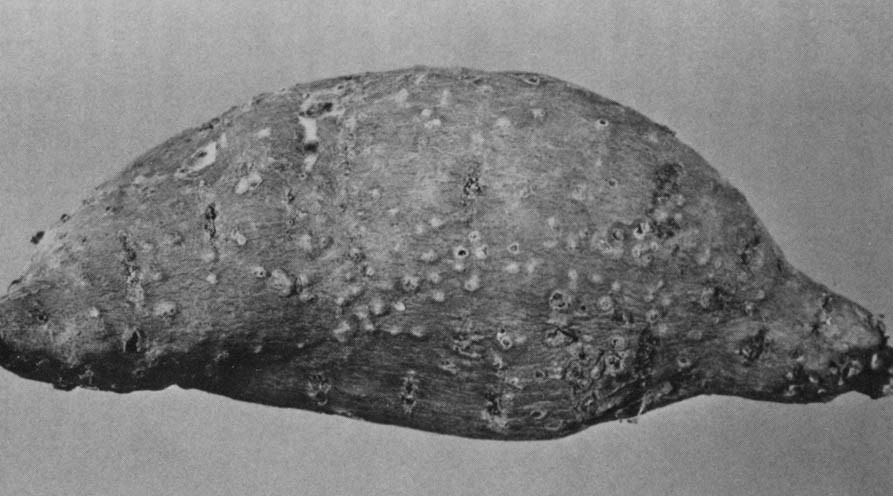

Small blister-like bumps are sometimes apparent on the storage root

surface, where nematodes are embedded (G. Philley)

Egg

masses of M. incognita (R. Gapasin).

|